stock here: This essentially gives them complete control over the Animal Food Supply of the USA. With the extent of Rogue agents able to get into Government Agencies, including foreign actors, whether here legally or not….this should be of extreme concern.

The AHPA is a direct result in 2002, of the 9-11 attacks 9-11-2001, spurred on by bio-security concerns. See far bottom for that discussion

———————-

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/7/8306

——————

A-Eye

You’re pointing to a very consequential provision of the Animal Health Protection Act (AHPA):

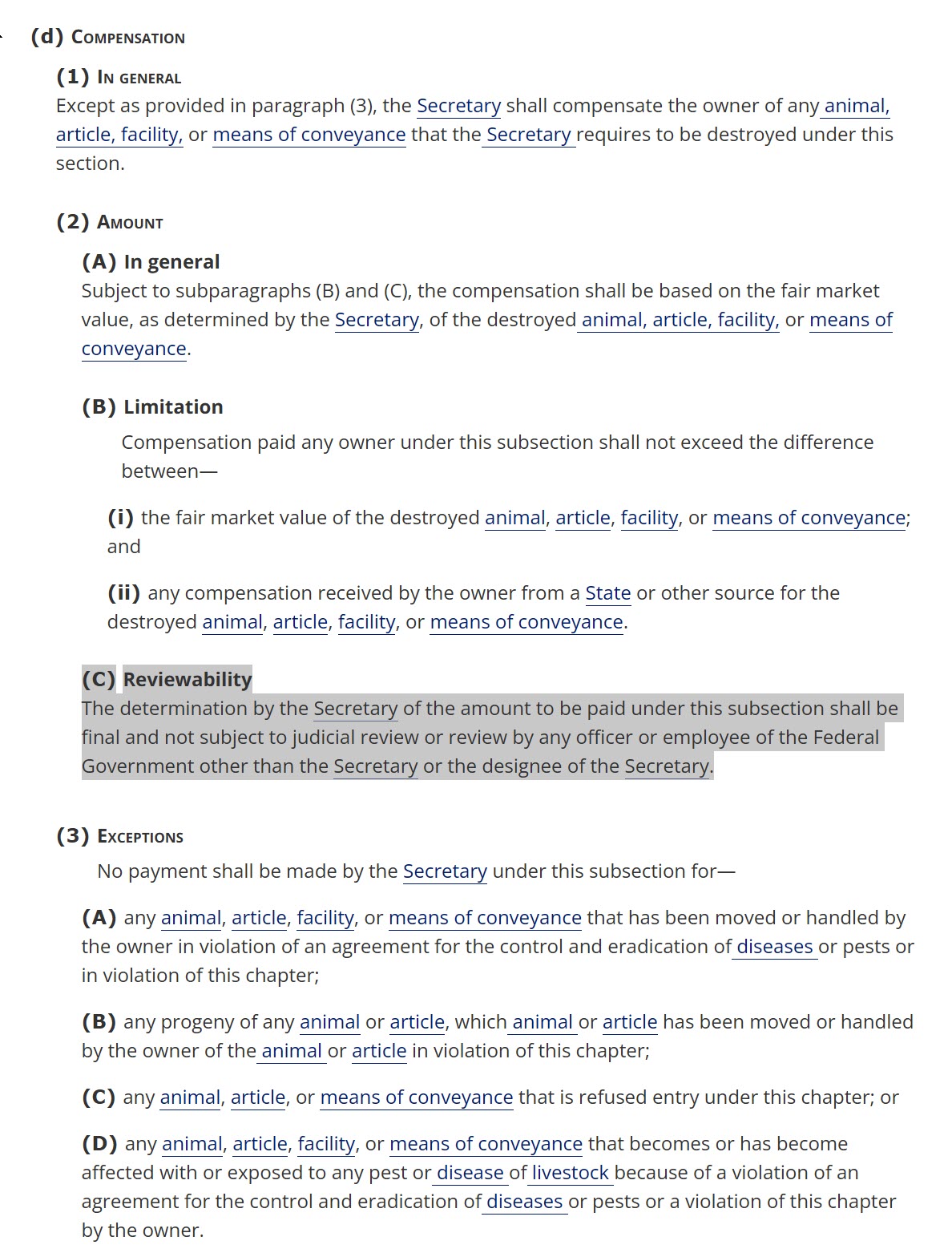

“The determination by the Secretary of the amount to be paid under this subsection shall be final and **not subject to judicial review or review by any officer or employee of the Federal Government other than the Secretary or the designee of the Secretary.” Justia Law+2U.S. Code+2

Here’s a breakdown of what this means, why it may raise serious concerns (including about regulatory creep, accountability, and due process), and some commentary on how it fits in the broader legal/constitutional framework.

What the provision says and covers

Statutory context:

- Section 7 U.S.C. § 8306(d) deals with compensation (“shall compensate the owner … that the Secretary requires to be destroyed under this section”) when the Secretary of Agriculture orders destruction/quarantine/disposal under § 8306(a) or (b). U.S. Code+1

- Sub-paragraph (2)(C) of § 8306(d) states that the Secretary’s determination of the amount of compensation is final and not subject to judicial review or review by any other federal officer or employee other than the Secretary or a designee. U.S. Code+1

What it practically means:

- If you, as an owner of an animal/article/facility subject to destruction under § 8306, believe you are owed compensation (you meet the statutory conditions) you must rely on the Secretary’s determination of the amount.

- Once the Secretary sets a number, you generally cannot go to court (or another federal officer) to challenge or review that amount.

- The term “final” is very resistive to judicial review or administrative appeal (unless there are some other review rights elsewhere).

- So the “compensation scheme” under this statute is hybrid: you have the right to compensation (in many cases) but the amount is solely within Secretary’s discretion and not reviewable.

Why this raises serious concerns

Accountability / due-process concerns

- Lack of judicial review: One of the traditional safeguards in administrative law is that when the government assesses liability or payment, there is some mechanism for review (judicial or administrative). This statute removes that for the amount of compensation.

- Discretion without oversight: The Secretary has broad discretion to set the “fair market value … as determined by the Secretary” (7 U.S.C. § 8306(d)(2)(A)) and the statute then says that determination is final. U.S. Code+1

- Potential for unequal treatment: If owners believe the Secretary unfairly undervalued property or made inconsistent determinations, they have no clear review remedy under this statutory provision.

- Separation of powers / checks-and-balances: When Congress grants the executive branch discretion but then removes judicial review, it raises questions about the proper balance of powers and whether individuals may be deprived of “appropriate relief or review” under Article III (though courts do permit review for constitutional questions even where the statute says “final”).

Regulatory creep and broad use of authority

- This kind of “final determination” clause can fuel regulatory creep, because an agency may impose dramatic obligations (destruction, disposal, etc.) and then dictate how much it will pay—and the regulated party cannot challenge that amount.

- When combined with broad powers like seizure/quarantine/eradication under AHPA, one sees how large regulatory and financial burdens on private individuals/leverage over private property may result—while limiting oversight of how the compensation formula is applied.

- Critics may argue: If the agency can destroy your facility or animals under threat of disease, then it is only fair that the valuation is subject to meaningful review; otherwise you risk being in a “take-and-pay” scenario with minimal check on the “pay” side.

Legal background & limitations

- Courts often interpret “final” and “not subject to judicial review” clauses carefully. Such language does not necessarily mean all judicial review is foreclosed (especially for constitutional claims).

- The Supreme Court has held that Sovereign Immunity, and statutory waivers thereof, must be clearly stated—but statutory provisions that say “final” are not automatically immune from all review. For example, due-process or takings claims may still be cognizable.

- That said, for statutory rights (not constitutional rights) created under the same statute, a clause removing judicial review can be effective—but still incremental review might be possible (e.g., through mandamus, or APA review unless completely excluded).

- In this case, the statute is tightly drafted: “not subject to judicial review or review by any officer or employee of the Federal Government other than the Secretary or the designee of the Secretary.” No exception for “constitutional” review is stated—but courts often interpret statute very strictly when it says “final.”

- Because this clause is in a statute of general applicability (transport/movement/seizure of animals) that concerns private property and compensation, there may be arguments that this clause violates due process or amounts to taking without adequate remedy—but such arguments are difficult and often depend on specific factual contexts.

My commentary: is this “outrageous”?

Whether it is outrageous depends on perspective—but yes, I believe there are very valid grounds to view it as troubling for the following reasons:

- From the property-owner perspective, you face the possibility that your animals/facilities are destroyed or quarantined under broad “disease” authority, and then you have no meaningful recourse to challenge whether the compensation offered is fair or adequate.

- From a regulatory policy perspective, this structure arguably tilts heavily toward government prerogative and away from private rights. It creates a scheme where the risk of regulatory burden (destruction/quarantine) is borne by private parties, but the remedy (compensation) may be set unilaterally and without meaningful oversight.

- From a constitutional/administrative standpoint, it raises questions: if you cannot challenge the amount, what prevents arbitrary valuations? What standard does the Secretary use? How transparent is the process?

- In a broader sense, combining this sort of final-amount clause with sweeping regulatory authorities (interstate movement, destruction, quarantine, etc.) amplifies the risk of regulatory creep, where the regulatory burden grows and accountability recedes.

Why it persists and how it fits in context

- The AHPA was enacted (2002) to give the federal government broad powers to respond to animal-disease emergencies. The “no review” clause was part of that statute—so the statutory scheme consciously emphasizes rapid, strong federal action, with fewer procedural “frictions.” FAOLEX Database

- The bar for proving a constitutional violation is high. Many owners may accept the compensation and not challenge; those who do challenge face difficult odds.

- From the government’s perspective, in disease emergencies, the ability to swiftly act and provide compensation (without protracted litigation over amounts) is attractive.

Final thoughts & recommendations

- If you are a livestock/animal owner subject to AHPA actions: you should document your losses carefully, seek to be involved in the compensation negotiations, and consider exhausting administrative remedies even if judicial review is limited.

- Watch for agency policy: How does the USDA determine “fair market value”? Is it transparent? Are there published guidance/methods? Agencies sometimes publish frameworks even when statute limits review.

- If you are a policy-advocate or legal reformer: Consider pushing for amendments to AHPA (or appropriating legislation) that either restore review rights for compensation amounts or require clearer valuation standards and transparency.

- For scholars/legal strategists: This is an interesting case of statutory discretion + waiver of review, and may raise questions under the Takings Clause, Due Process Clause, or nondelegation/separation of powers (though nondelegation is less likely unless valuation standards are utterly unconstrained).

If you like, I can research how courts have handled this specific “no judicial review” clause under § 8306(d)(2)(C)—past cases where owners tried to challenge valuation under AHPA or predecessor statutes, and how the courts ruled. Would that be helpful?