stock here, hat tip to Oldster

I copied much of the article “summary” which in itself becomes book-like. I tried to get AI to summarize the lions share of the article, but was rejected as too long. When I finally toned it down, it flagged a “This content may violate our usage policies.” but even so it did provide a summary, here:

https://www.unz.com/article/solzhenitsyns-two-hundred-years-together/

https://openai.com/policies/usage-policies

The usage policy is above, it seems straight forward, although except for talking about Jews (not mentioned in the usage policy) I don’t see anything else that would flag this excerpt.

o sane person wants to lie. Aside from whatever harm lying might cause, lying also chips away at a person’s dignity. Knowing that your words will quickly mold to a model other than Truth somehow cheapens you — as if any model will do. Expediency, authority, greed . . . it’s hard to think of circumstances under which lying about non-private matters doesn’t cheapen a person. Put person X under these conditions, and he’ll say whatever you want him to say. How’s that for a human being? Nothing exalts more than knowing that your words will serve Truth and only Truth.

Dissidents often struggle with this when discussing the Jewish Question. We want to tell the truth. On the other hand, our message would be much more powerful if only we could omit this inconvenient fact or embellish that disappointing one. As dissidents, we wish to put forth a realistic depiction of Jews, without spite or bias, to uncover their net negative impact on our politics, and, to a lesser extent, our culture. This is the first step to freeing ourselves from the Jewish yoke, so to speak. And if we are telling the truth, then we can afford to show more than one side of the story and still be persuasive.

This seems to encapsulate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s approach to the Jewish Question as it relates to Russia in his classic text Two Hundred Years Together. In this volume (which is still not properly translated into English), Solzhenitsyn reviews the history of Russian Jewry and places much of the blame for the October Revolution, the atrocities of the early Soviet period, and subversive Left-wing behavior in general squarely on the shoulders of Jews. He also, perhaps most importantly for him, exonerates much of Tsarist Russia from the charge of anti-Semitism which never seems to stop oozing from Jewish pens. That a writer of Solzhenitsyn’s towering stature took on a project which directly refutes the myth of perpetual Jewish victimhood and reverses the blame typically reserved for white gentiles should be nothing less than a triumph for the Right. Relatively minor figures who write and speak on the Jewish Question — as brilliant as they often are — can be deplatformed, smeared, and ultimately ignored. Solzhenitsyn, on the other hand, was for several years in the 1970s the most famous dissident in the world. Since his death in 2008, his reputation as an author, historian, Christian, and patriot remains impeccable. He cannot be so easily ignored.

Dissidents on the Right should therefore piggyback on Solzhenitsyn’s fame and use his name as often as possible when combating the Left on the battlefield of ideas — especially when it comes to the Jewish Question. And this is where Two Hundred Years Together comes in.

But what if this would be a misuse of Two Hundred Years Together? Despite what many of his more hysterical critics say, Solzhenitsyn was no anti-Semite. There are many passages in this work that show justice, even tenderness, towards Jews. He does have great respect for them. He just wishes to set the record straight — a record that the Jews themselves have warped with their abuses of history.

But what if sticking scrupulously to the Truth as Solzhenitsyn does won’t be enough? What if the Jews themselves rarely do this and will not hesitate to publish material of questionable scholarship but unquestionable defamation against whites simply because it is in their ethnic interests to do so? In fact, it is a common trope among Jewish writers such as Bernard Lewis (Semites and Anti-Semites), Robert Wistrich (Antisemitism: The Longest Hatred), and Daniel Goldhagen (The Devil that Never Dies), and many others to speak about anti-Semitism not as a rational response to Jewish hegemony but as if it’s an a priori evil in the black hearts of white gentiles.

Despite being profoundly dishonest, this approach works. It holds sway among the Jews themselves and since World War II has helped to browbeat the West into submission to Jewish ethnic interests.

In an example of how Solzhenitsyn does not take this approach in Two Hundred Years Together, he frequently cites Jewish author Josef Biekerman who comes across as Solzhenitsyn’s Semitic doppelganger. He is ethnocentric yet willing to speak out about the abuses of power in which his own people indulge (which Solzhenitsyn does to great extent in his Red Wheel opus). As co-founder of the Patriotic Alliance of Russian Jews in the 1920s, Biekerman vowed to combat Bolshevism not merely because he feared it would increase anti-Semitism but also because he empathetically felt that it would be bad for Russia and Russians. His colleague Isaak Levin openly called for an examination of the Jewish role in the October Revolution. Jewish writer Danil Pasmanik, who authored a book about the Jews and the Russian Revolution, professed heartfelt concern for the “unending sorrow of the Russian citizen,” and stated that Jews “cannot flourish while the country disintegrates around us.” The book these men published, Russia and the Jews, challenges Jews, especially radical, secular, Left-wing Jews, to reject the evil in their hearts.

“It is time we understood that crying and wailing . . . is mostly [evidence] of emotional infirmity, or a lack of culture of the soul . . . You are not alone in this world, and your sorrow cannot fill the entire universe . . . When you put on a display, only your own grief, only your own pain, it shows . . . disrespect to others’ grief, to others’ sufferings.”

These were truly righteous Jews, and Solzhenitsyn admires them not only for their honesty and compassion, but also because of their lack of self-hate (a theme he discusses at length in his essay “Repentance and Self-Limitation in the Life of Nations” in his From Under the Rubble collection). Unfortunately, Biekerman, Levin, Pasmanik, and others like them were voices in the wilderness when it came to mainstream Jewish opinion. They seemed to accomplish little other than to inflame resentment among other Jews. They were accused of “attack[ing] their own compatriots,” and were smeared as “anti-Semites” and “enemies of the Jewish people,” and so on. Solzhenitsyn recognizes the tragedy in this, but also seems too enamored with the possibility of rapprochement between Russians and Jews to become as aggressive towards Jews qua Jews as the Jews themselves were to Biekerman, Levin, and Pasmanik.

I must admit, this is tempting, given how the majority of Jews don’t behave like the enemy of whites and have contributed greatly to Western culture through their talent, energy, and capital. It is very easy to admire them when imagining men like Josef Biekerman being the rule rather than the exception. Many convincing arguments can be spun from this false supposition.

In Two Hundred Years Together, Solzhenitsyn is essentially more concerned about telling the truth than winning the argument.

Over a decade after his death, however, white dissidents in the West are beginning to realize that they can no longer afford to be correct if being correct is not enough to win the argument — that is, to persuade a critical mass of whites of the necessity of counter-Semitism. We are swiftly losing our majorities in our homelands to hostile invaders who wish ultimately to subjugate us — and, sadly, many wealthy and influential Jews remain on the vanguard of this invasion. Even more sadly, the majority of diaspora Jews, if their voting patterns tell us anything, actually support this invasion. Perhaps if Russia in the 1990s had been more like Western Europe of the 2020s, Solzhenitsyn would have written Two Hundred Years Together with a little more urgency.

This is not to be critical of Solzhenitsyn. The value and importance of Two Hundred Years Together cannot be overstated. Along with The Gulag Archipelago, it is perhaps his most important non-fiction work. Rather, I suggest that the Dissident Right use Two Hundred Years Together as a weapon against Jews — even if Solzhenitsyn himself would have disapproved of this tactic. Can we afford not to? Perhaps if Jews like Josef Biekerman were the rule and not the exception we could. But sadly this is counter-factual. Therefore it makes sense to use the Jews’ insidious methods against them and focus on only those elements of Truth which suit our argument. This is a cultural war, after all, and since when is it considered honorable to tell the truth to your enemy during war?

What follows is a simple accounting of the most noteworthy Jewish misdeeds found in Two Hundred Years Together. Not included will be the more common historical tropes involving Jews, for example as usurers, pimps, alcohol merchants, and unscrupulous exploiters of the poor. Also not included will be the many entertaining pages Solzhenitsyn dedicates to nineteenth-century Jews as tax cheats, draft dodgers, grievance mongers, and shockingly incompetent agriculturalists (the latter being part of the Russian government’s futile efforts to assimilate its Jewish population). Finally, we won’t include all the instances in which the Tsar or the Russian government either gave in to the demands of revolutionaries or acted on behalf of the Jews. Instead, we will focus mostly on the acts of terror and atrocity attributed to Jews during the Soviet and pre-Soviet periods, which were of most immediate interest to Solzhenitsyn. These periods should be of most immediate interest to modern dissidents as well, given how the leftward lurch of Russian society in 1900s, 1910s, and 1920s is finding an eerie analog in the West a century later.This is not to be critical of Solzhenitsyn. The value and importance of Two Hundred Years Together cannot be overstated. Along with The Gulag Archipelago, it is perhaps his most important non-fiction work. Rather, I suggest that the Dissident Right use Two Hundred Years Together as a weapon against Jews — even if Solzhenitsyn himself would have disapproved of this tactic. Can we afford not to? Perhaps if Jews like Josef Biekerman were the rule and not the exception we could. But sadly this is counter-factual. Therefore it makes sense to use the Jews’ insidious methods against them and focus on only those elements of Truth which suit our argument. This is a cultural war, after all, and since when is it considered honorable to tell the truth to your enemy during war?

Perhaps when confronted with the twin myths of Jewish innocence and victimhood, this information could help convince the uninitiated of the lies and hatred which bolster both. And for the initiated, the knowledgeable, the dissident, perhaps the most trenchant passages in Two Hundred Years Together will arm him or her with the information which could help spark the counter-Semitic revolution that is so desperately needed in the West today.

• • •

Chapter Six: In the Russian Revolutionary Movement

Despite being poorly represented among Left-wing radicals prior to the 1870s, Jews quickly grew in prominence among them during the 1870s. Students such as V. Yokhelson, A. Zundelevich, Mark Natanson, Leon Deutsch, and others became energetic organizers of the revolutionary movement. Solzhenitsyn notes how almost none of these Jews supported revolution due to poverty — they, in large part, came from wealthy families. He also notes how, unlike Christian revolutionaries, few Jewish ones suffered a break from their families because of their activities. On the whole, Jewish parents — regardless of their occupations — tolerated their children’s subversive activities. These revolutionaries quickly turned from their religious, patriarchal, and traditionalist roots after the slightest contact with Russian culture. Egalitarian nihilism made it too tempting for them. In many ways, Solzhenitsyn blames assimilation with Russians for bringing out the worst in Jews. And while demonstrating that these early Jewish revolutionaries had tremendous drive and talent, he also describes how mentally unbalanced many of them were.

After the 1881 assassination of Tsar Alexander II and the widespread pogroms which followed, however, a critical mass of Jews then rose to pursue one goal: “the destruction of the current political regime.” Jews rapidly established international networks dedicated to Marxist and socialist revolution, and these networks had a profoundly negative impact upon Russia. In fact, during the 1880s and 1890s, Russian revolutionaries began to rely more and more on Jews as “detonator[s] of revolution.” The revolutionary movement became disproportionately Jewish. Marxist historian M. N. Pokrovsky estimated that by the late nineteenth century, Jews (who made up less than five percent of the population of Russia) made up between a quarter and a third of all the revolutionary parties. In 1903, Russian statesman Sergei Witte told Zionist Theodore Herzl that Jews constituted no less than half of all revolutionaries. In 1905, General N. Sukhotin, the commander of Russian forces in Siberia, calculated that of all the political prisoners exiled to Siberia, thirty-seven percent were Jews. Solzhenitsyn also cites various Jewish sources that attest to the heavy Jewish involvement in the revolutionary movement during the pre-Soviet period.

Chapter Nine: During the Revolution of 1905

In this chapter, Solzhenitsyn demonstrates how ravenous Russia’s Jewish population had become for armed conflict with the Tsarist regime by the turn of the twentieth century. The belligerence on display is shocking not only for its own sake, but also because the Jews barely discuss it themselves. Because of this, this crucial episode has been left out of history almost entirely.

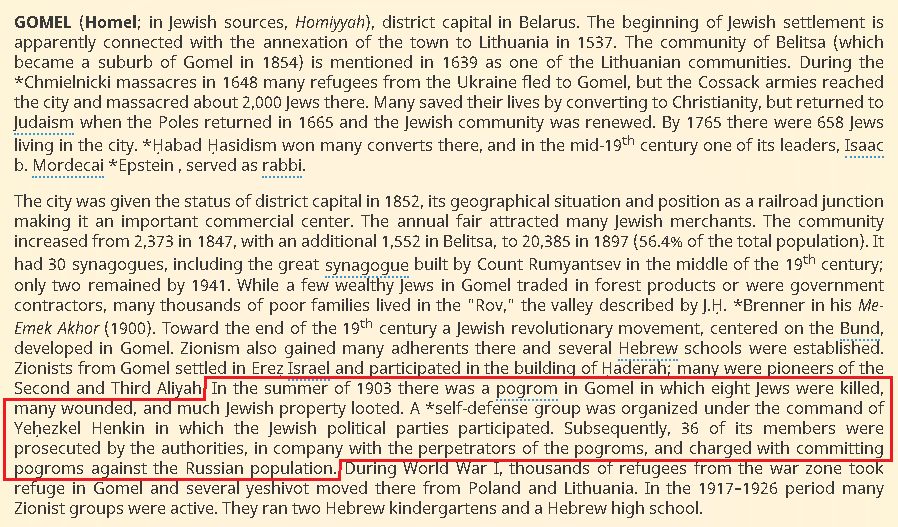

Solzhenitsyn dedicates several pages to the deadly 1903 pogrom in Gomel, Belarus. While the official investigation by the Russian authorities claimed that Jews and Russians alike shared blame for the violence, Solzhenitsyn, using contemporaneous police reports, shows that armed and organized gangs of Jews had instigated the pogrom against Russians. These groups had been formed by the Bund, which previously that year had organized a festival celebrating the anniversary of Tsar Alexander II’s assassination. During an argument between a Jew and a Russian peasant in an outdoor market, the Jew spat in the face of the Russian. A brawl ensued, during which the surrounding Jews blew whistles, a clear sign for attack. Soon enough, the place was swarming with armed Jews, who beat the outnumbered Russians mercilessly, men, women, children, and elderly alike. Solzhenitsyn describes how a Jew snuck up behind a Russian and stabbed him in the neck, killing him. In another instance, a Russian girl was dragged down the street by her hair. And when the police arrived, the Jews fired live rounds and hurled stones at them. This went on for a day, and all the casualties were Russian. What’s worse for the Jewish victimhood narrative, when the troops arrived, their main purpose was to protect the wealthy Jewish part of town from Russian reprisals — and to show their appreciation, the Jews fired shots and threw stones at them too.

Of course, the reason why the Jews were so irate at that point in time was because of the anti-Jewish pogrom in Kishinev in modern-day Moldova, a few months prior. But modern dissidents should not concern themselves with this. Why? Because Jews rarely consider the reasons behind any anti-Jewish actions taken by gentiles, pogroms or otherwise. For them, such behavior simply springs from irrational gentile minds. This is how Jews weaponize history. Well, thanks to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, two can play at that game.

From the Jewish Virtual Library, an example of how Jews weaponize history by presenting only that information that suits their ethnic interests.

Several times in Chapter Nine, Solzhenitsyn relays how Jews instigated conflict by firing their revolvers at police as well as by committing acts of terror and attacking innocent Russian peasants and workers. He names Nissel Farber — who threw a bomb at a police station, killing two and wounding three — and Aron Eline — who threw a bomb at police, wounding seven. He describes several other similar attacks by Jewish terrorists. This kind of provocation immediately invalidates any claim to Jewish innocence and Jewish victimhood.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, the new breed of Jewish radical became much more influential and radical than before. Solzhenitsyn labels Grigory Gershuni and Mikhail Gotz as terrorists and describes how they and others took charge of many of the revolutionary parties throughout Russia, especially the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR). Gershuni oversaw the assassination of two governors and Minister of the Interior Dmitry Sipyagin as well as one failed assassination attempt. While these revolutionaries often relied on Russian assassins, one of their primary bomb makers was Jewish. Solzhenitsyn seizes upon the irony of the Jew Pinhas Rutenberg, who trained Jewish terrorists in Russia and oversaw the execution of the double agent priest Georgy Gapon, and then moved to Palestine, became an engineer, and brought electricity to the region. “There, he shows that he is capable of building,” Solzhenitsyn writes, “but in his early years, in Russia, he certainly does not work as an engineer. He destroys!” Jews also made up the great bulk of theorists who would tirelessly propound anarchism, socialism, and other disruptive ideologies. These ideologies often took on religious proportions. And although the most active of these Jewish terrorists were young, Solzhenitsyn points out how the older generations of Jews continued to tolerate or support them.

Prior to the failed revolution of 1905, the Bund had actually declared war on Russia in one of its proclamations:

The revolution has begun. It burned in the capital, its flames covering the whole country. . . . To arms! Storm the armories and seize all the weapons. . . . Let all the streets become battlefields!

The press and the local orators echoed this sentiment. Solzhenitsyn relays an incident involving a Russian soldier who returned home to Moscow after being held in captivity in Japan:

At the mere sight of this officer in battle dress, the welcome which he received from the Muscovite crowd was expressed in these terms: “Spook! Suck up! The Tsar’s lackey!” During a large meeting in the Theater Plaza, “the orator called for struggle and destruction”; another speaker began his speech by shouting” “Down with the autocracy!” “His accent betrayed his Jewish origins, but the Russian public listened to him, and no one found anything to reply to him.” Nods of agreement met the insults uttered against the Tsar and his family; Cossacks, policemen, and soldiers, all without exception — no mercy! And all the Muscovite newspapers called for armed struggle.

One final anecdote in this damning chapter. Solzhenitsyn tells of an Alexander Schlichter, a Jewish revolutionary, who instigated a railway strike that paralyzed rail traffic to several cities, including Moscow. This Schlichter had also made threats to Kyiv workers to go on strike, raised money from students to purchase arms, and established “flying detachments” whose purpose was to disrupt the city of Kyiv to “prepare the armed resistance to the forces of order.”

This Alexander Schlichter ultimately became a Bolshevik and was, years later, the Agriculture Commissioner in Ukraine during the time of the Holodomor, in which over fifteen million people perished.

Solzhenitsyn states it succinctly: “The revolutionary effervescence that had seized Russia was undoubtedly stirred up by that which reigned among the Jews.”

The Duma, Partisan Press, & Beilis Trial

Chapter Ten: The Period of the Duma

Despite including little by way of terrorism or atrocity, chapter ten is one of the most revealing and fascinating chapters in all of Two Hundred Years Together. It simultaneously demonstrates both Jewish perception and distortion of reality, and just how devastating this can be.

The chapter begins with Tsar Nicholas’ October Manifesto of 1905 which, among other things, promised basic civil rights to all Russian citizens and established the Russian parliament known as the Duma. This, and the establishment of the first Russian constitution a year later, signified the ongoing liberalization of the Russian government, which was following similar changes among the Russian intelligentsia. And this leftward shift, slow and ponderous as it was, allowed the Jewish Question to be openly discussed and considered more than ever.

Yet when hearing the truculent rhetoric of the Duma and its significant Jewish element — as well as that of the Jewish-run Russian press — it would seem as if Russia were backsliding in feudalism. Jewish interests were represented largely by the Cadet Party (“Cadet” being the informal name of the Constitutional Democratic Party), both with Jewish representatives coming from the Pale of Settlement and their allies among the Russian intelligentsia. Solzhenitsyn describes the Cadet Party as the juncture where the groups mingled freely. Their stated goal was equal rights, especially for Jews. Nevertheless, the Tsar’s appointment of Pyotr Stolypin as Prime Minister belied how disingenuous the Duma really was.

Under Stolypin, real measures had been taken to alleviate restrictions placed upon Jews. Stolypin himself had limited ability in this regard, since the Tsar in 1906 had expressed sympathy for the Jewish cause but insisted that reforms must be implemented by the Duma. Despite having implemented administrative measures to ease restrictions upon Jews and believing that pro-Jewish policy in general would deter Jewish radicalism, Stolypin had no choice but to comply. Yet, ironically, the Duma refused! The Tsar and Russian Prime Minister, the two most powerful men in the empire, had given its parliament — and, by extension, its pro-Jewish Cadet Party — freedom to legislate Jewish equality, and the parliament chose not to. Why?

Difficult to explain this other than by a political calculation: the aim being to fight the Autocracy, the interest was to raise more and more the pressure on the Jewish Question, and to certainly not resolve it: ammunition was thus kept in reserve. These brave knights of liberty reasoned in these terms: to avoid that the lifting of restrictions imposed on the Jews would diminish their ardor in battle. For these knights without fear and without reproach, the most important, was indeed the fight against the power.

Between the lines, we should read that one should never take the Left, especially the Jewish Left, at its word. Any Progressive agenda is merely a smokescreen for destroying traditional gentile power structures and replacing them with totalitarianism. Solzhenitsyn also notes the irony behind Stolypin’s assassination at the hands of the Jew Mordko Bogrov — as well as the Russian Jewish community’s tacit approval of the assassination. In fact, Bogrov’s father, despite being a wealthy capitalist himself who had benefited greatly from the Russian system, publicly declared that he was proud of his son.

Cheering on the Duma’s refusal to create a smooth transition to equal rights for Jews was the Jewish-run press. In many ways, Solzhenitsyn’s description of how Jews dishonestly manipulate public opinion to serve their own ethnic interests presages how they do the same thing today in the West. This indicates that this could very well be a fundamental characteristic of Jewish diaspora news media which traverses centuries and thousands of miles. Solzhenitsyn describes how the newspapers “systematically distorted the debates in the Duma, largely opening their columns to the deputies of the left and showering them with praise, while to the deputies of the right they allowed only a bare minimum.”

The predominance of Jews among the press corps covering the Duma became a running joke after a Right-wing deputy referred to the press box as “this Pale of Settlement of the Jews” in a speech.

Solzhenitsyn sums up the destructive nature of the Jewish-run press thusly:

The following statement was attributed to Napoleon: “Three opposition papers are more dangerous than one hundred thousand enemy soldiers.” This sentence applies largely to the Russo-Japanese War. The Russian press was openly defeatist throughout the conflict and in each of its battles. Even worse, it did not conceal its sympathies for terrorism and revolution.

This press, totally out of control in 1905, was considered during the period of the Duma, if we are to believe [former Russian Prime Minister Sergei] Witte, as essentially “Jewish” or “semi-Jewish”; or, to be more precise, as a press dominated by left-wing or radical Jews who occupied key positions. In November 1905, D. I. Pikhno, editor in chief for twenty-five years of the Russian newspaper The Kievian and a connoisseur of the press of his time, wrote: “The Jews . . . have bet heavily on the card of revolution . . . . Those, among the Russians, who think seriously, have understood that in such moments, the press represents a force and that this force is not in their hands, but in that of their adversaries; that they speak on their behalf throughout Russia and have forced people to read them because there is nothing else to read; and as one cannot launch a publication in one day, [the opinion] has been drowned beneath this mass of lies, incapable of finding itself there.”

Solzhenitsyn ends this chapter with the way in which the Jewish press covered the famous Beilis Trial from 1911. Similar to the Dreyfus Affair from earlier in the century, a most-likely innocent Jew was charged with a crime — in this case the torture, mutilation, and murder of a 12-year-old boy — in an atmosphere steeped in classic anti-Semitism. The murder occurred on the property of a Jewish-owned factory, and quickly blood libel accusations were being made by the local population. This led to the arrest of factory worker Menahem Beilis. Solzhenitsyn chronicles many of the bizarre twists of the investigation and ensuing trial, and admits that not only was the prosecution’s case dubious, but Beilis was accused in large part because he was Jewish.

Beyond the person of Beilis, the trial turned in fact into an accusation against the Jewish people as a whole — and, since then, the atmosphere around the investigation and then the trial became superheated, the affair took on an international dimension, gained the whole of Europe, and then America.

So we have an innocent Jewish defendant, corrupt and incompetent gentile authorities, and a vengeful, seemingly anti-Semitic, gentile public. This was, in effect, the perfect storm in which the Jewish press could lose all of restraint, and Solzhenitsyn provides some examples. Ultimately, an all-gentile (and mostly peasant) jury acquitted Beilis. But this, of course, did not exonerate the Russians of anti-Semitism in the eyes of Jewish writers. Note how Bernard Lewis, in his Semites and Anti-Semites, describes the affair:

Another case . . .was the arrest in 1911 of a Jewish brickmaker called Mendel Beilis, in Kiev in the Ukraine, for the ritual murder of a Christian boy. This followed after the temporary halting of the pogroms in Russia under both international and domestic liberal pressures, and represented a new effort and a new direction on the part of the anti-Semites, by now entrenched at the highest reaches of the imperial Russian government. Two years were spent in preparing the case, which was concocted by an anti-Semitic organization, in cooperation with the minister of justice and the police. It was opposed by an impressive array of Russian liberals and socialists, including such figures as the writer Maxim Gorki and the psychologist Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. The trial opened at the end of 1913, and, like the Dreyfus trial in France, became the focus for a conflict between opposing political forces in Russia, and the cause of widespread protests in the democratic countries of the West. It was no doubt partly because of the latter that the trial ended in an acquittal of the accused, “for lack of evidence,” and with no decision on the question of ritual murder.

So clearly, the entire Beilis Affair can be wrapped up in Lewis’ simplistic Jew Good-Gentile Bad paradigm. Indeed, there is some truth behind the claim that the whole thing was a regrettable mess that brought out the worst on both sides. And, it must be said that Beilis does appear to have been innocent.

However, the tremendous value of Solzhenitsyn’s analysis emerges when we see how he includes information that Lewis and others do not. Not only did finding this information require some legwork. It also evinces a keen understanding of the weaknesses behind the Jewish narrative. First, Solzhenitsyn shares with us the truly bizarre and horrific nature of this murder.

. . . there are forty-seven punctures on his body, which indicate a certain knowledge of anatomy—they were made to the temple, to the veins and arteries of the neck, to the liver, to the kidneys, to the lungs, to the heart, with the clear intention of emptying him of his blood as long as he was still alive, and in addition — according to the traces left by the blood flow — in a standing position (tied and gagged, of course).

So, this outrage, combined with the fact that the victim was a child, could perhaps explain the heated reactions from the local community better than anti-Semitism can. Jewish writers like Lewis would want one to believe that this was a run-of-the-mill murder. It most definitely was not.

Second, Solzhenitsyn offers a coda to this affair which utterly undresses the myth of Jewish innocence and victimhood. While Beilis emigrated, ultimately to the United States, and died of natural causes at age sixty, other players in this affair were not so lucky. During the early Soviet period, the now-former Russian Justice Minister (whom Lewis mentions above) was shot by the Bolsheviks. The prosecutor was sent to a concentration camp, after which his fate is unknown. And, in 1919, Vera Cheberyak, a witness for the prosecution, was interrogated over her role in the Beilis affair by Jewish Chekists. After refusing to change her testimony and denying that she had been bribed, she was summarily executed.

As with much of volume two of Two Hundred Years Together, Solzhenitsyn demonstrates how Imperial Russia was highly imperfect under the Tsars, but remains far superior in many respects to the Soviet Union — one of which obviously being criminal justice. Gentiles wrongly accuse a Jew, but still give him his day in court and acquit him, and Jews everywhere scream and protest. Later, Jews don’t give a gentile her day in court — and, even worse, blow her brains out with a pistol shot — and Jews say nothing.

With this kind of double standard, how can we trust the Jewish narrative on anything?

It seems to make sense that Lewis would dishonestly exclude such salient information in his cursory analysis of the Beilis trial. It would undermine his philo-Semitic, anti-gentilic agenda, something Solzhenitsyn does quite well in Two Hundred Years Together.

Solzhenitsyn takes one final, well-aimed dig at the press:

Beilis was acquitted by peasants, those Ukrainian peasants accused of having participated in the pogroms against the Jews at the turn of the century, and who were soon to know the collectivization and organized famine of 1932-1933 — a famine that journalists have ignored and that has not been included in the liabilities of this regime.

Smashing the Balance

By the time the reader begins the second volume of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Two Hundred Years Together, he’s aware of a complex yet fragile balance established by the author in volume one. Jews and Russians have shared the same empire and language for centuries, but not without conflict brought about by their different natures and the exigencies of history. Solzhenitsyn takes pains to remain objective despite his clear sympathy for the Russian point of view. Often, when he reveals the misdeeds of Jews, he demonstrates how Russians are not without sin either. The first three chapters of the second volume (thirteen through fifteen), however, smash this balance and reveal Solzhenitsyn almost desperately trying to maintain it as if reconstructing a house of cards while it crumbles. These chapters span the two revolutions of 1917 and mark the culmination of changes among Russian Jewry which began in the 1870s — a change that took Russian Jews from calculating self-interest and detachment to assimilation, radicalism, and ultimately wanton destruction. The historical material is too damning to view it any other way. It embarrasses any attempt at evenhandedness. Solzhenitsyn never stops making them, of course. But knowing what’s coming in the years ahead — the Russian Civil War, the terror famines, the gulags, and the Great Terror, among other things — it becomes impossible to walk away from Two Hundred Years Together and not lay disproportionate blame for the catastrophe that was the Soviet Union upon the shoulders of Jews.

Solzhenitsyn makes it clear that one of the first orders of business for the victors in the February Revolution was Jewish equality and a ban on anti-Semitism. Anyone who showed even the slightest fealty towards the Tsar, Christianity, the old Russian Empire, and, by extension, Russian culture, history, or identity, was at the very least suspect. Right away, things improved for the Jews. With so many of them already in the cities, and with so many of them sympathetic to the Revolution, it should come as no shock that a multitude of professional opportunities opened up for them practically overnight. Jewish groups proliferated in the cities and the military. Jewish enthusiasm ran high, especially abroad, where financiers such as Jacob Schiff, the Rothschilds, Baron Ginzberg, and others gave millions to the cause. Tens of thousands of Jews returned to Russia to take part in the Revolution. At the same time, however, the fledgling government began hunting known judeophobes, including the prominent men who presided over the infamous Beilis trial from several years earlier.

The Right, in general, was also targeted for cultural annihilation. Rightist newspapers were forced to close down for accurately reporting the links between the Bolsheviks and the Germans during World War I. Even more insidiously. . .

[t]he chairman of the Union of the Russian People, Dmitry Dubrovin, was arrested and his archive was seized; the publishers of the far-right newspapers Glinka-Yanchevsky and Poluboyarinova were arrested too; the bookstores of the Monarchist Union were simply burned down.

And, of course, Jews were everywhere. Solzhenitsyn describes how, during his exhaustive studies of the February Revolution and the memoirs of its participants, many Jewish names leaped out at him. He provides several eyewitness accounts that corroborate this observation, including one from V. D. Nabokov (the novelist’s father). An American pastor named Simons, who was in Petrograd during the revolution, testified before the US Senate that

. . . everywhere in Petrograd you could see groups of Jews, standing on benches, soap boxes, and such, making speeches . . . There had been restrictions on the rights of Jews to live in Petrograd, but after the Revolution, they came in droves, and the majority of agitators were Jews.

Solzhenitsyn also produces numbers to support these claims. Among the thirty active members of the Executive Committee of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in Petrograd immediately after the Revolution, more than half were Jews and fewer than one quarter were Russians. Solzhenitsyn also points out that at the Socialist Revolutionary Congress of May and June 1917, thirty-nine of the 318 delegates were Jews (over twelve percent). Of the Central Committee elected during that Congress, seven out twenty were Jews (thirty-five percent). In April 1917, Jews made up a third of the Central Committee of the Bolsheviks. They also comprised a majority of the revolutionaries in those two trains which sped through wartime Germany towards Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. One of those trains contained Lenin. In October 1917, when the decision was made to launch the Bolshevik Revolution, Solzhenitsyn lists six Jews among the twelve conspirators. After the Revolution, a young Lazar Kaganovich destroyed the photographic evidence of the Council of the Assembly of Leningrad, explaining that “the vast majority of the presidium at the table were Jews.” And, of course, Jews made up a clear half of the first Soviet Politburo. It must be remembered that at that point in history, Jews made up less than five percent of the Russian population.

A small pile of Bolsheviks had now come to power and taken authority, but their control was still brittle. Whom could they trust in the government? Whom could they call on for aid? The seeds of the answer lay in the creation in January 1918 of a special People’s Commissariat from the members of the Jewish Commissariat, the reason for which was expressed in Lenin’s opinion that the Bolshevik success in the revolution had been made possible because of the role of the large Jewish intelligentsia in several Russian cities. These Jews engaged in general sabotage, which was directed against Russians after the October Revolution and which proved extremely effective. Jewish elements, though certainly not the entirety of the Jewish people, saved the Bolshevik Revolution through these acts of sabotage. Lenin took this into consideration, he emphasized it in the press, and he recognized that to master the state apparatus he could succeed only because of this reserve of literate and more or less intelligent, sober new clerks.

Thus, the Bolsheviks, from the first days of their authority, called upon the Jews to assume the bureaucratic work of the Soviet apparatus — and many, many Jews answered the call. They in fact responded immediately.

As typical in Two Hundred Years Together, Solzhenitsyn provides names — and these go well beyond the famous ones such as Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev. Here we have the Jewish second tier. Under normal circumstances, minor figures such as Arkady Rozengolts, Simon Nakhimson, Zorach Greenberg, Yevgeny Kogan, and many others would hardly be worth remembering except for historians. But in Two Hundred Years Together, they become pawns on the great Jewish Question chessboard.

Throughout these three chapters, however, the reader can see Solzhenitsyn struggling to maintain his evenhandedness. His efforts get more strained as time goes on. At first, he simply denies the Jewish role in the February Revolution. “[N]o, the February Revolution was not something Jews did to the Russians, but rather it was done by the Russians themselves, which I believe I amply demonstrated in The Red Wheel.” Of course, there is much truth in this. The shortsightedness, corruption, laziness, and incompetence of the Russian leadership at the time is impossible to deny. But rarely does Solzhenitsyn attribute this downfall to outright malice. The Russians, such as Alexander Kerensky, who contributed to the first Revolution were atypical Russians, while the Jews who became revolutionaries were typical Jews.

The February Revolution was carried out by Russian hands and Russian foolishness. Yet at the same time, its ideology was permeated and dominated by the intransigent hostility to the historical Russian state that ordinary Russians didn’t have, but the Jews had.

Often in this part of the work, Solzhenitsyn remarks on the dominant “foreign element” among the revolutionaries aside from Jews — Poles, Latvians, Georgians, even Chinese. Solzhenitsyn seems to argue against himself even further when he discusses the ethnic makeup of the shadowy Executive Committee (mentioned above) which was formed only hours after the February Revolution and was indeed the real power behind the Provisional Government. The Committee’s first act was to seize control of the Russian Army. This organization was over half-Jewish, although it attempted to obscure this fact through pseudonyms. At the time, no one knew who was really ruling Russia. Despite this, Solzhenitsyn wavers between laying blame upon the foreign element, which was acting behind the scenes after the February Revolution, and the Russian element, which should have prevented the Revolution in the first place. Ultimately, he punts on this quandary, refusing to ascribe definitive blame in either direction.

This is unconvincing, largely due to Solzhenitsyn’s profound understanding of the Jewish Question and his genius for argument. This emerges during his discussion of otshchepentsy (отщепенцы), which can be translated to mean “traitor to one’s blood and heritage.” Looking back to the revolutions of 1917, many Jews no longer deny their shamefully disproportionate participation. Instead, they endeavor to slip themselves off the hook by claiming that Trotsky and the others were otshchepentsy — not real Jews, but renegade Jews. As evidence, they will point to the not insignificant number of Jews who were also victims of the Bolsheviks. Solzhenitsyn, for argument’s sake, accepts this, but then wonders why these same Jews hesitate to apply the otshchepentsy excuse to non-Jews, and Russians in particular, for similar misdeeds.

Solzhenitsyn also notices a pattern. Jews just happen to produce a lot of otshchepentsy, don’t they? Yes, there were Russians like this, but proportionately far fewer. Solzhenitsyn also asks the delicate question of how these otshchepentsy were received by their own people at the time, and not years later when embarrassed historians find the need to make excuses for their deceased countrymen. And, sadly, the majority of Jews during the time of the 1917 revolutions did not renounce their so-called otshchepentsy. Quite the opposite, actually. Solzhenitsyn states that there are modern Israeli historians who interpret the October Revolution as a great triumph of Jewish spirit and identity.

So much for otshchepentsy.

It seems that Solzhenitsyn’s fighting spirit gets the better of him towards the end of chapter fifteen. The same author who halfheartedly exonerated the Jews vis-à-vis the February Revolution now states that they were the driving force behind the October Revolution. Further, he reminds us that the clearly pro-Jewish stance of the Provisional Government made this second revolution entirely unnecessary for the welfare of Russian Jews. They had already achieved equality and were on track to surpass the former Russian elites in power and influence if they hadn’t already. Why did they need the October Revolution if not for unlimited power or the annihilation of Russia? In a powerful passage, Solzhenitsyn quotes a Jewish author who believes that the Jewish Bolsheviks “willfully destroyed their own souls.”

Solzhenitsyn ends this powerful chapter with a direct call for Jews everywhere to take responsibility for their past, and to renounce their “revolutionary thugs” and their “endless ranks who went into Bolshevik service to commit mass murder.”

How do we Russians take responsibility for the pogroms, for those merciless peasant arsonists, for the mad revolutionary soldiers and sailor beasts, and the Jews get to spread their hands in blameless innocence over the countless Yiddish names among the commissar-butchers who commanded the whole wretched business?

Solzhenitsyn has absolutely no time for this blatant double standard. Still, he wants nothing more than to meet the Jews halfway in this repentance and self-limitation of nations. But he insists that it be mutual. And why not? If the Jews don’t hold up their end of the bargain, then the Russians (or anyone else) have no reason to hold up theirs. And this would be a tragedy, because, according to Solzhenitsyn, without the obligation of responsibility and a true understanding of the past, all sense of national identity will be lost.

The Russian Civil War

Solzhenitsyn points out early in chapter sixteen of Two Hundred Years Together that immediately after the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks wielded fearsome, unchecked power. And it was the wanton abuse of this power that led to the unspeakable violence of the Russian Civil War and the anti-Jewish pogroms to which Russian history had no equivalent.

Right away, the Red Army was a Jewish creation. Leon Trotsky, along with Ephraim Sklyanksy and Jacov Sverdlov, founded it in 1918 with many Jews in leadership positions. Solzhenitsyn cites several Jewish sources and spends pages naming names. The first Soviet secret police, known as the Cheka, was also disproportionately Jewish in its leadership (especially in places like Kyiv where there were many Jews to begin with), as it was also disproportionately non-Russian. Trotsky himself is on record admitting to this. Solzhenitsyn names names in the Cheka as well.

He also points out how dedicated to terror the Cheka really was. The early days of the Russian Civil War Solzhenitsyn describes not as a war but as the “liquidation of a former adversary,” and the Cheka was the weapon used to effect this. It held the Russian population in mortal fear. It routinely enforced the death penalty without trial. It captured and executed innocent hostages by the thousands (sometimes by mass drownings in barges). Whenever bothering to interrogate suspects, their concern was not to reveal incriminating evidence, but to discern the suspects’ heritage and social class. One’s identity was enough to determine guilt or innocence in the jaundiced eyes of the Cheka. Solzhenitsyn quotes a certain (presumably Jewish) Schwartz promoting nothing less than genocide:

The proclaimed Red Terror should be implemented in a proletarian way. If physical extermination of all servants of Czarism and capitalism is the prerequisite for the establishment of the worldwide dictatorship of proletariat, then it wouldn’t stop us.

Solzhenitsyn quotes a Cheka order to annihilate entire villages and execute their populations. He relays estimates that in Crimea from 1917 to 1921, Red forces murdered 120,000 to 150,000 people. During the Russian Civil War, Crimea became known as the “All-Russian Cemetery.” He also includes a Jewish source who remarks on the striking change which Jewish youth underwent after the Revolution:

We were astonished to find among the Jews what we never expected from them — cruelty, sadism, unbridled violence — everything that seemed so alien to a people so detached from physical activity; those who yesterday couldn’t handle a rifle, today were among the vicious cutthroats.

Things become murky, however, in Ukraine. The Revolution and the resulting Red Terror met with great resistance there. Reactionary forces, represented mostly by the White Army, had their share of victories before their ultimate defeat. And with victory, as was the case during this time, came atrocity. In many places, Jews were blamed for the rise of Bolshevism. This resulted in a series of pogroms that dwarfed the ones of the late nineteenth century. Between 1917 and 1921, an estimated 180,000-200,000 Jews were murdered in Ukraine and what is today Belarus — but not entirely by White forces. The Red Army (believe it or not) as well as various partisan groups (often Ukrainian nationalists who fought against both White and Red) were responsible for nearly eighty-five percent of this. The remainder was caused by the Whites.

Solzhenitsyn vividly describes the horror:

Sometimes during the anti-Jewish pogroms by rebellious peasant bands, entire shtetls were exterminated with indiscriminate slaughter of children, women, and elders. After the pogromists finished with their business, peasants from surrounding villages usually arrived on wagons to join in looting the commercial goods which were often stored in large amounts in the towns because of the unsettled times. All over Ukraine rebels attacked passenger trains and often commanded communists and Jews to get out of the coach and those who did were shot right on the spot; or in checking papers of passengers, suspected Jews were ordered to pronounce “kukuruza” [кукуруза, the Russian word for corn] and those who spoke with an accent were escorted out and executed.

(Note the similarity to the famous Shibboleth episode in the equally bloody Book of Judges from the Old Testament. Coincidentally, the ancient Hebrew word Shibboleth meant an ear of corn.)

Outrages such as these accelerated the Jewish shift to the Left and forced the majority of centrist or neutral Jews to embrace the Reds. Can anyone blame them? Could this have been helped? Could any middle ground have remained during such a turbulent period? After the October Revolution, how could the average Russian peasant, now armed and part of an army, not be seething in hatred for Jews — the very people they believe stole their country from them? In fact, Solzhenitsyn describes the White Army as being “hypnotized by Trotsky” and believing that their country was now being occupied solely by Jewish Commissars.

But there was a non-insignificant number of patriotic Jews who were either sympathetic with the White cause or had actually joined White forces. Solzhenitsyn makes this point often. He also stresses how not all White forces were hostile to Jews. Rather, many tended to remain suspicious of even friendly Jews given how prominent other Jews were among the Reds. And so, in many cases, Jewish allies were either rejected or forced into humiliating supporting roles during the war. Some White generals forbade pogroms entirely, such as Alexander Kolchak in Siberia and Pyotr Wrangel in Crimea.

Sadly, this wasn’t enough. In the West, the pogroms soured public opinion of the Whites and crippled their ability to raise much-needed funds. Winston Churchill, then Britain’s Secretary of War, was sympathetic to the Russian nationalist cause, and wrote to White General Anton Denikin, explaining that the pogroms were making it difficult for him to secure support for the Whites in Parliament. Churchill also feared the influence of British Jews who were already making up a substantial portion of the British elite. Of course, the Bolshevik press took full advantage of every pogrom and did much to manipulate world opinion away from the Whites. That equally enormous Soviet atrocities did little to sway world opinion in the other direction is a testament to how tightly the Jews controlled world media even back then.

It’s a rigged game, this public opinion. Jews make ostentatious victims, but as victimizers, they lurk in the shadows like assassins. This is the two-faced beast all Rightists must face, and was something the White forces may not have understood well enough.

That being said, pogroms and a persistent, almost superstitious, Jew-hate may not have been all that doomed the Whites to defeat. But according to Solzhenitsyn, they were significant factors. When he writes that the Whites were hypnotized by Trotsky, he isn’t exaggerating much. For example, wild conspiracy theories about Trotsky worshipping the Devil and practicing Satanic rituals in the Kremlin persisted in White circles for years after the war. Without pogroms at the very least, the Whites would have been able to raise more money and make more use of Jewish talent and manpower than what they had at their disposal at the time. They also would have made Bolshevism a lot less attractive to centrist or otherwise neutral Jews. And, who knows? This might have made the difference in the war’s outcome.

White racial dissidents today can learn much from this regrettable episode. The Russian Civil War is a unique time in history since it is where racial nationalism, petty nationalism, the Left, and the Jewish Question all meet at a bloody crossroads. How could the forces of Reaction have survived this encounter? How could some semblance of normalcy have been restored in the former Russian Empire? My reading of chapter sixteen of Two Hundred Years Together tells me that a sober appreciation for the Truth — and a good deal of restraint — would have gone a long way. The enemy is the Left — in this case, the Bolsheviks. The driving force behind this enemy is, as always, the Jewish Left. But not all Jews are on the Left, and not all of the Left is Jewish. This, of course, does not mean that the Dissident Right need curry favor with Jews or even with the relatively small subset of them that is favorably disposed to Dissident Right perspectives.

What this does mean, however, is threefold:

- All-consuming hatred is unhealthy, immoral, and bad in and of itself. This should be an axiom not just in war but in life.

- All-consuming Jew-hate plays into the Left’s strengths. In any struggle against the Left, Rightist or Reactionary forces must understand that the propaganda war and the war on the ground are equally important. In at least three of the great Left-Right conflicts of the twentieth century (The Russian Civil War, World War II, and the Vietnam War) the propaganda war made the difference in favor of the Left. This is what the Left — especially the Jewish Left — is really good at. They’re much better at propaganda than the Right is, in fact. When taking the Left on, the Right needs to understand this and behave accordingly, even if the Left doesn’t have to behave accordingly. This is the price the Right has to pay for coming in second when it comes to propaganda.

- Any Rightist movement in conflict with the Left should do as little as possible to alienate centrist or neutral Jews. Again, this does not mean the Right should seek these people out or curry favor with them. Unabashed philo-Semitism is simply a bad look for any leader of the Right. It seems that a professed Judeo-neutral position might be the best course. It makes the radical Left less attractive, it makes Leftist propaganda harder to fabricate, and it will allow for the Right to utilize a certain amount of Jewish capital, talent, and manpower.

Solzhenitsyn laments at the end of the chapter that the hard swing of Jews towards Bolshevism and the hard swing of the Whites against the Jews “eclipsed and erased the most important benefit of a possible White victory — the sane evolution of the Russian state.”

The Bloody Red Pill

Large numbers of Jews who did not leave after the revolution failed to foresee the bloodthirstiness of the new government, though the persecution, even of socialists, was well underway. The Soviet government was as unjust and cruel then as it was to be in 1937 and 1950. But in the Twenties the bloodlust did not raise alarm or resistance in the wider Jewish population since its force was aimed not at Jewry.

Having contributed greatly to defeating the Whites in the Russian Civil War, many Soviet Jews spent the 1920s consolidating their positions within the Soviet government apparatus. In chapter eighteen of Two Hundred Years Together, Solzhenitsyn, in typical comprehensive fashion, reveals how extensive their dominance during this period really was. He calls upon contemporaneous sources which claim that in 1927 Jews made up nearly twelve percent of the Soviet government in Moscow, twenty-two percent in Ukraine, and over thirty percent in Belorussia. Much of this can be explained by the general enthusiasm many Russian Jews had for the young republic, their large presence in the major cities, and their innate intelligence and talent. This does not, however, explain the active discrimination against Russians that took place during the same time, especially in universities. This also does not explain how Jews in government consistently used their influence to aid other Jews in quasi-official ways or how the law encouraged Jews to register complaints about anti-Semitism. Most insidiously, this does not explain how non-Jews who remarked upon or criticized the disproportionate Jewish presence in government ran the risk of being labeled counter-revolutionary. And counter-revolutionaries, Solzhenitsyn reminds us, could very well come in contact with nine grams of lead.

Despite Jews making up only 5.2 percent of the Communist Party in 1922, Jewish per capita party membership (7.2 percent) was nearly double that of Russians (3.8 percent). In leadership positions among the Communists, however, the Jews truly distinguished themselves. According to Pravda in the same year:

. . . at the 11th Communist Party Congress, Jews made up 14.6 percent of the voting delegates, 18.3 percent of the non-voting delegates, and 26 percent of those elected to the Central Committee at the conference.

Pravda, 1930:

The portrait of the 25-member Presidium of the Communist Party included eleven Russians, eight Jews, three from the Caucasus, and three Latvians.

Solzhenitsyn describes how, in the state security organizations, Jewish membership increased during the 1920s. Three of the four of OGPU director Felix Dzerzhinsky’s assistants were Jews: Genrikh Yagoda, Benjamin Gerson, and M. M. Lutsky. Solzhenitsyn spends several pages describing the careers of people such as Lev Zalin, Leonid Bull, Simeon Schwartz, and the Nakhamkins clan (Hasidim from Gomel who “thirsted for revenge on everyone”). The Soviets staffed their diplomatic delegations largely with Jews — something the Western Europeans could not help but notice. Even among lower-level provincial authorities, Jews were disproportionately represented. As usual, Solzhenitsyn provides pages worth of names.

Of course, the Russian populace began to notice the brilliant success of so many Jews within the government of their barbaric new republic. They noticed the overall Jewish enthusiasm for the USSR. They noted how, as a group, Jews were the only nationality that seemed to enjoy a net benefit from the Revolution. Jews received the best land, the most privileges. They were less likely to be seen waiting in lines. Although there were efforts to suppress Judaism, Zionism, and Jewish culture (as there was with all religions and ethnic identities at the time), the Christians seemed to get the worst of it, with clergy being murdered or sent to gulags by the thousands, and their churches ransacked or destroyed. Solzhenitsyn describes how, in 1918, a Russian Orthodox procession came forth from the Kremlin in Tula in Central Russia and was simply gunned down.

This naturally caused a great deal of anti-Jewish feeling, especially in the countryside. When prominent Jews Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev, and Lev Kamanev formed their United Opposition against Stalin after Lenin’s death, most of their followers were Jewish. Trotsky fretted how Stalin might use the growing anti-Jewish feelings among the populace against his Jewish rivals. There may have been some truth to this, but Stalin was too politically astute to resort to crass anti-Semitism himself — especially given how numerous Jews were in the Party and how Western opinion and support of the Soviet Union depended much upon its treatment of Jews. As such, his most trusted Jewish allies, Lev Mekhlis, Moses Rukhimovitch, and Lazar Kaganovich never left his side during this time.

Solzhenitsyn also leaves us with this unsubtle nugget:

At the 12th Communist Party Congress (1923), three out of six Politburo members were Jewish. Three out of seven were Jews in the leadership of the Komsomol and in the Presidium of the All-Russia Conference in 1922. This was not tolerable to other leading communists and apparently preparations were begun for an anti-Jewish revolt at the 13th Party Congress (May 1924). There is evidence that a group of members of CK [Central Committee] was planning to drive leading Jews from the Politburo, replacing them with [Viktor] Nogin, [Aleksandr] Troyanovsky, and others, and that only the death of Nogin interrupted the plot. His death, literally on the eve of the Congress, resulted from an unsuccessful and unnecessary operation for a stomach ulcer by the same surgeon who dispatched [Mikhail] Frunze with an equally unneeded operation over a year and a half later.

It should be noted that in 1925 Mikhail Frunze was a rising star among the Soviets and was considered a possible successor to Lenin. Although he also suffered from a stomach ulcer, he said he was in fine health when Stalin pressured him into having this operation. Whether or not the physicians who performed this operation were Jewish remains an open question, but rumors persist among those who preserve Frunze’s memory that they were.

Towards the end of chapter eighteen Solzhenitsyn states unequivocally that Jews could be found throughout the Soviet power structure during the 1920s when that same power structure was stripping freedoms of speech, commerce, and religion from its citizens.

The 1930s, which Solzhenitsyn covers in chapter nineteen, was a different beast. This and the following chapter indeed are the bloodiest red pills found in Two Hundred Years Together. Terror famines, the Great Terror, and the worst abuses of the gulag system lay ahead. The “sinister principal executive” behind the mass collectivization which starved millions in Ukraine and other places, was Yakov Yakovlev-Epshtein. For many years this killer was lionized in the Soviet press. Solzhenitsyn lists three of his Jewish collaborators. He discusses Isai Davidovich Berg, the NKVD murderer who invented the mobile gas chamber. He implicates Jews such as M.G. Gerchikov (chairman of the Grain Trust board of directors), M. Kalmanovich, and I. Kleiner for their important roles in Soviet agriculture during the worst months of the Holodomor. Jews also comprised a third to a half of the People’s Commissariats of Trade and Supply during this time. Despite offering the caveat that Jews never populated one hundred percent of these powerful organizations, Solzhenitsyn goes on for pages detailing the Jewish dominance of Soviet economics, diplomacy, culture, and politics during the 1930s. He lists dozens of Jews by name who were victims of Stalin’s purges and describes the list as a “commemoration roster of many top-placed Jews.”

Here is a typical passage from chapter nineteen:

Out of 25 members in the Presidium of the Central Control Commission after the 16th Party Congress (1930), 10 were Jews: A. Solts, “the conscience of the Party” (in the bloodiest years from 1934 to 1938 was assistant to Vyshinsky, the General Prosecutor of the USSR); Z. Belenky (one of the three above-mentioned Belenky brothers); A. Goltsman (who supported Trotsky in the debate on trade unions); ferocious Rozaliya Zemlyachka (Zalkind); M. Kaganovich, another of the brothers; the Chekist Trilisser; the “militant atheist” Yaroslavsky; B. Roizenman; and A.P. Rozengolts, the surviving assistant of Trotsky. If one compares the composition of the party’s Central Committee in the 1920s with that in the early 1930s, he would find that it was almost unchanged — both in 1925 as well as after the 16th Party Congress, Jews comprised around 1/6 of the membership.

In the upper echelons of the communist party after the 17th Congress (“the congress of the victors”) in 1934, Jews remained at 1/6 of the membership of the Central Committee; in the Party Control Commission — around 1/3, and a similar proportion in the Revision Commission of the Central Committee. (It was headed for quite a while by M. Vladimirsky. From 1934 Lazar Kaganovich took the reins of the Central Control Commission). Jews made up the same proportion (1/3) of the members of the Commission of the Soviet Control. For five years filled with upheaval (1934-1939) the deputy General Prosecutor of the USSR was Grigory Leplevsky.

And this was occurring when Stalin was supposedly purging Jews from the Party.

In chapter twenty, Solzhenitsyn returns to his focus on the gulag system. This, understandably, is a short chapter given the vast, three-volume Gulag Archipelago which preceded it. However, Solzhenitsyn focuses on the Jewish Question here in the way he did only tangentially in Gulag. For example, he states that Jews had it easier than non-Jews in the gulag, and that they tended to make up the upper strata in these places. They deliberately looked out for each other and used their influence at the expense of non-Jews. For example, they were known to recruit other Jews for privileged positions among medical staff, even if the recruits had no medical training. Solzhenitsyn, again, spends pages listing Jews by name who used their tribal affiliations to receive unfair advantages in the gulag system — some of whom even had the nerve to complain about it later. He also retells the story of Ane Bernstein, an ethnic Latvian who believed his fortunate name was his ticket to salvation while a zek. He claimed that in all his camps, Jews took him for one of their own and never failed to help him when he needed it.

Solzhenitsyn reserves particular contempt for Lev Inzhir and Naftaly Frenkel. The former was a stool pigeon and false informant who became the chief accountant of the gulag system. Inzhir used his Jewish connections in government shamelessly to improve his position in the camps while presiding over the suffering of untold Russians, Ukrainians, and others. The latter was a successful businessman residing in Constantinople who had escaped Russia before the Revolution. He was no communist. Yet, he returned to the Soviet Union anyway and, as chief manager of the labor force of Belomor Canal, was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands. Both Inzhir and Frenkel were covered extensively in Gulag.